Crowdfunding as neighborhood storytelling

(This article is cross-published as part of a series on civic crowdfunding with the Civic Paths research group.)

Raising money is one objective for crowdfunding, but not the only one. Every crowdfunding attempt also performs a story. How does crowdfunding shift neighborhood stories of place?

For civic engagement in neighborhoods, collective stories are essential. According to a decade of neighborhood research, collective action depends on stories to shape our collective imagination. Levels of civic engagement go up when neighborhoods have strong storytelling connections, especially across local media, residents, and neighborhood nonprofits. (Full disclosure: this research comes from USC’s Metamorphosis Project, where I am an affiliated researcher.)

Already, crowdfunding has targeted some weird “neighborhood stories.” Consider the project to build Detroit an ambassador statue… of Robocop! The Kickstarter project was successfully funded for more than $50,000 in March of 2011, with more than 2000 contributors. Although the cost was beyond Detroit’s mayor, it was “not too much for the world to fund.”

Too sci-fi and trivial? Keep in mind that the Statue of Liberty was also crowdfunded, with more than 100,000 micro-donors. To fund the Statue of Liberty, a mainstream newspaper served as the platform to raise awareness and funnel donations. Detroit’s Robocop used Kickstarter, the largest crowdfunding service. Does donating as a crowd help us to collectively imagine?

Detroit and the United States are also imagined communities. Both are real — the term ‘imagined’ was coined by Benedict Anderson partly to recognize the power of collective identity. For Anderson, this power was most visible in the volunteers who risked their life to fight for their country. By contrast, Detroit has been branded as an epicenter for young social entrepreneurs to come and attempt community transformation.

Robocop and the Statue of Liberty have character, ready for drama. They serve as place branding, but they can also support more participatory civic storytelling. Countless people have appropriated the Statue of Liberty for activism, to tell their own story and advocate for a collective good.

Literal bridges can also serve as public metaphors. Consider the Luchtsingel project in Rotterdam, which can translate as “canal of air.” Their crowdfunded bridge is a 350-pedestrian connection from the city center to the run-down neighborhood of Hofbogen.

At first glance, the bridge is a product: more than 1,300 people contributed by symbolically purchasing boards for the bridge. Yet the crowdfunding aligns with the way stories unfold, building tension before resolution. “By phasing the building process, the actual Luchtsingel becomes visible step by step, which allows for people to become involved and anticipate the effects of the end product” (from an article titled “architectural activism”).

Big players in Cities are trying out crowdfunding for economic development. Last week concluded a bold experiment in Chicago, called Seed Chicago. The group highlighted 11 neighborhood projects on a curated page for Kickstarter. About half were funded.

The problem is equity. At the city scale, there are far too many stories – too many communities. Most will be left out, which reinforces trauma for communities that have been historically marginalized. In other words, a story is told when projects fail. Failure stories undermine the self-efficacy that is vital for community health. From this perspective, a 50% funding rate could have a net negative effective on the civic engagement of neighborhoods.

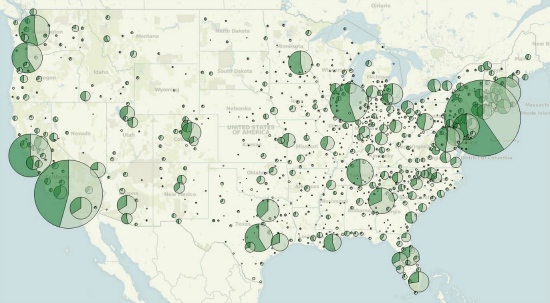

Worse, the geography of crowdfunding is unequal. According to a network analysis of Kickstarter, success is not just a referendum on project quality, but the extent of your social network. The diagram below shows the geography of successful projects, and its ties to a city’s concentration of creative individuals (see blog and journal article). Equity at the neighborhood level is presumably just as rampant.

The most equitable place for storytelling may still be the physical streets. The challenge for Seed Chicago projects was that they lacked tactics to bridge the participation gap between the digital and the physical. Storytelling on the streets is more equitable, with no special technology needed to access public space. Public art and festivals reach broad audiences, and the neighborhood stories they tell are easy to join. The streets may not scale cheaply, but they are still some of the best places to meet strangers, and build neighborhood trust. Will Seed Chicago help residents who lack tech skills to join the crowdfunding (and its incentive payoffs)? Not without extra support. One solution is to seek the right kind of stories that can cross-pollinate between digital recruiting and the streets.

Stories that bring people to physical streets must break through the clutter — they need drama, with a narrative arc that rises and falls. That’s right: they fall, and so mobilizing stories may best be kept distinct from the ongoing delivery of services and the need for sustainable revenue. Right now, crowdfunding itself is novel enough to be a story — but that will fade. The sustainable approach to crowdfunding may be to sidestep day-to-day funding, and instead to seek story-based engagement that raises neighborhood expectations, sparking participation for a new vision.

Last month in Las Vegas, a project was funded for just $8,000 to take over an empty block in downtown. They declared, “for this one weekend we’re transforming the block into a living community.”

Their language was strong: “we want to show that when all of us come together as a community we can change our neighborhoods. We can change our towns. We can change our cities. We want to show that when we join our skills, talents, experiences and resources together we can create the kind of Las Vegas we all want to live in.” This, for social scientists, is the language of collective self-efficacy.

Perhaps the shift for cities is to blend the department of cultural affairs with economic development. Can tech novelty help connect the crowd to physical streets? This is exactly what happened in Austin, Texas with the Payphone Revival project ($6000 raised in April of 2012). The goal was to “restore function and communicative potential… creating meaningful interactions between pedestrians and their everyday surroundings.”

The group found 10 artists on their own, raised almost 50% of the money in connection with the City’s cultural arts division, and then turned to the crowd to help with the rest. The project is staged not only to secure funding but to tell a sequential story. But it’s less clear how the story will bridge crowd with community.

Too many projects treat the crowd as the community. Instead, we need stories and platforms that can connect the two.

Civic-only platforms are emerging for crowdfunding, but few integrate stories. Some serve government and infrastructure needs (like the impressive Neighbor.ly). Others celebrate amazing individuals and their projects (like Benevolent, or Donors Choose for education, which are both great). However, these platforms offer few supports to explicitly integrate storytelling networks, especially to connect with community-based organizations and media. For small one-off projects that may be fine. But when the goal is larger, at the level of neighborhood identity and community development, crowdfunding stories should strive to connect across networks of residents, networks of organizations, and local media. The civic platforms will continue to evolve; in the meantime, the burden for execution depends on campaign organizers who can weave transmedia and cross-network stories.

Are integrated stories fully possible, and at what budget? It’s probably still too early to say. In part, I wrote this blog to surface our internal debates for an ongoing project in LA, where we have just finished five weeks of community-based design. Our project seeks to reimagine the neighborhood payphone, and we call ourselves the Leimert Phone Company. Several of our teams are considering funding options, and all seek to deepen neighborhood networks. Can crowdfunding help us to tell a different story, building networks across crowd and community? No matter what our decision this summer, our criteria for success will center on neighborhood storytelling.

Are integrated stories fully possible, and at what budget? It’s probably still too early to say. In part, I wrote this blog to surface our internal debates for an ongoing project in LA, where we have just finished five weeks of community-based design. Our project seeks to reimagine the neighborhood payphone, and we call ourselves the Leimert Phone Company. Several of our teams are considering funding options, and all seek to deepen neighborhood networks. Can crowdfunding help us to tell a different story, building networks across crowd and community? No matter what our decision this summer, our criteria for success will center on neighborhood storytelling.

See also: the series overview on civic crowdfunding at the Civic Paths blog.